You are here

news

Flood plaques

A bumpy millennial relationship

Rome’s history runs parallel to that of the river that flows through it, ever since the legendary founding of the city: it was the Tiber perhaps in flood, 28 centuries ago, that carried the basket of Romulus and Remus to the spot where they were found by the she-wolf, at the base of the Palatine Hill. But in the relationship between the Romans and their river, love was never the only feature. It provided a wide range of benefits, no doubts about it, but it was also capricious, irascible and vengeful like any true deity, and as such it could not fail to arouse a certain guarded distrust, even a holy terror. For the repeated floods, first of all, which for more than two thousand years caused sometimes immeasurable damage to the city, exacting a heavy toll of blood and bringing with it, along with the stagnant water, a trail of disease and pestilence.

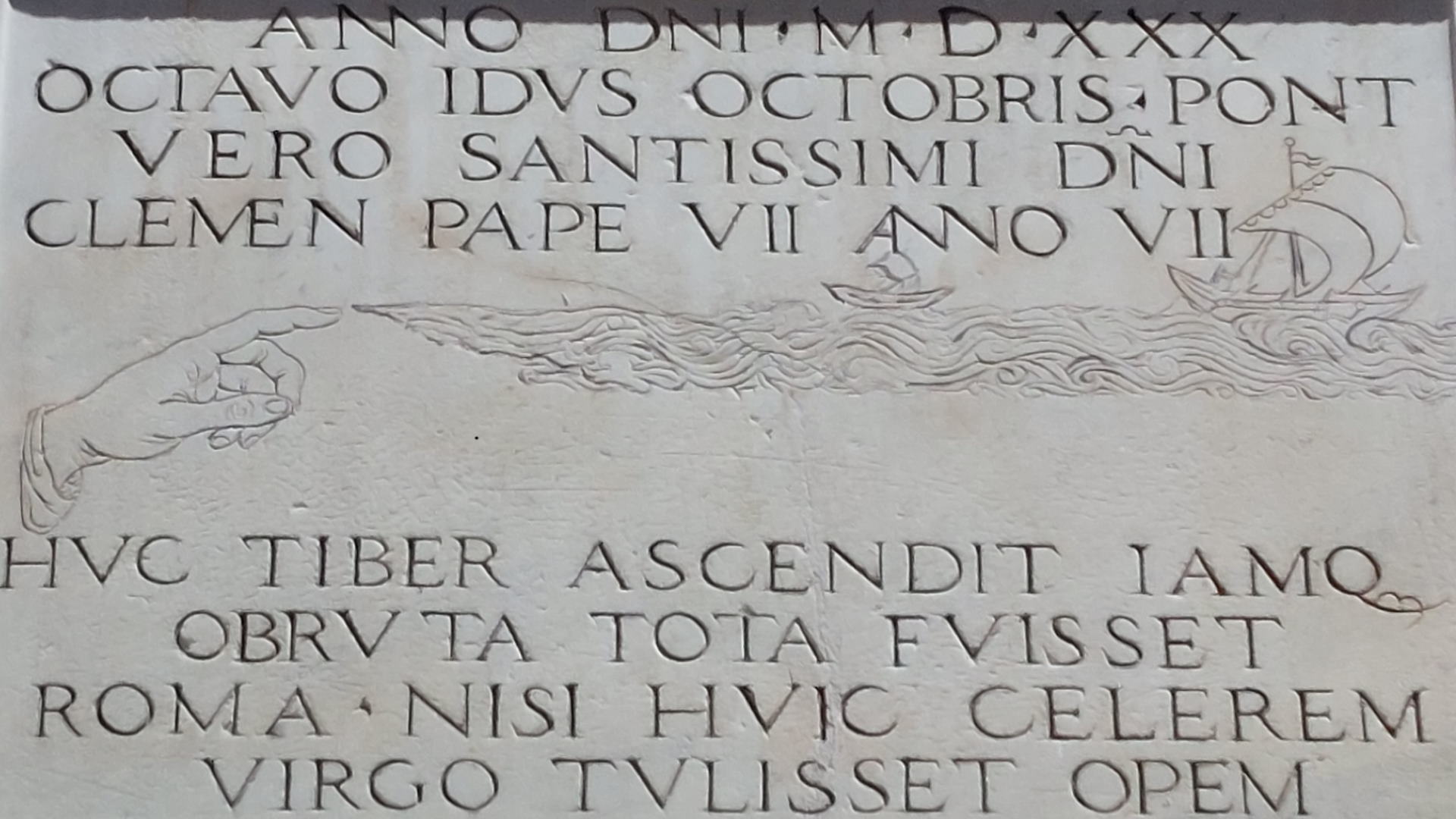

Huc Tiber ascendit

That is, so far the Tiber has risen. When fear gives way to amazement, it is only natural to want to hand down to posterity the exceptional nature of an event, to rewrite the record book. And so, sometimes half-hidden on the walls of churches, in the courtyards of buildings and on street corners, walking in the lowest parts of the city we will come across a large number of old plaques, made of marble or stone, that tell us about the unpredictability of the waters and their violence. More than 120 plaques, most of them preserved, were hung up to the 1930 to commemorate the floods: the simplest ones show only the flood’s month and year while in the most elaborate ones the waters are represented by wavy lines, with a stylized little hand indicating the actual level of the flooding on the wall. The oldest stone record of a flood dates back to 1180 and is engraved on a marble column, now in the Museum of Rome in Palazzo Braschi. Also no longer in its original location is the plaque in Gothic characters currently under a small arch at one end of Arco dei Banchi, once walled on the façade of the church of St Celso e Giuliano, close to Ponte Sant’Angelo: it recalls the flood of November 1277, the year in which floods began to be indicated with reliable and historically verifiable data.

Historical floods

The first plaque that still correctly reports the level reached by flood waters refers to the November 1422 flood and is located on the façade of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. It is in good company because the church, located in one of the lowest areas of the city where the water reached considerable heights, also preserves the memory of the floods of the years 1495, 1530, 1598 and 1870. Between the 15th and 18th centuries, the most devastating one was probably the Christmas flood of 1598, when the floodwaters reached a level of 19.56 meters at Ripetta, a record unsurpassed, submerging the columns of the Pantheon by as much as six meters and causing thousands of deaths. Nine mills were destroyed by the Tiber’s current, which even dragged away the corpses in the tombs of Santa Maria dell’Anima and swallowed three of the six arches of the ancient pons Aemilius, known at the time as Ponte Senatorio and from that day on renamed Ponte Rotto, the Broken Bridge. The damages were such that 12 plaques recall that day, for example at the entrance to Piazza del Popolo, on Via Santa Maria de’ Calderari and on the Lungotevere in Sassia. A further original testimony to the catastrophic flood is the Fountain of the Barcaccia: it is said that Bernini’s source of inspiration was a wreck of a barge dragged on that occasion by the flooding river as far as Piazza di Spagna.

The last roars

The last great floods date back to the 19th century. Plaques in Via dell’Arancio and Via Canova take us back to the 1805 flood, when the river invaded city areas from Ripetta to the Corso, reaching Piazza Navona, the Lungara and the Ghetto. The water also exceeded 16 meters in height on 10 December 1846, as evidenced by the plaque in the underground cemetery of the church of Santa Maria dell’Orazione e Morte on Via Giulia. The most tragic flood, however, was surely the one on 26-29 December 1870, three months after the breach of Porta Pia, when the waters exceeded 17 meters. The violence of the river, attested by some forty simple plaques, the victims and the damage made such an impression that King Victor Emmanuel II came to Rome for the first time and was prompted to adopt remedial measures. Based on a design by Raffaele Canevari, it was thus decided to build high retaining walls: finally finished in 1926, the so-called “muraglioni” walls put an end to the continuous and periodic danger, however, radically altering the entire Tiber environment and destroying unique landscapes and environments such as the ports of Ripetta and Ripa Grande. The last plaque is in the portico of San Bartolomeo all’Isola, decorated with a simple horizontal line and dating back to December 1937: the new walls contained the current and the waters caused only modest flooding.

The river Tiber

According to legend, the history of Rome begins right here

Pons Aemilius (Ponte Rotto - Broken Bridge)

Condividi

Condividi

The ancient mills on the Tiber

The Barcaccia Fountain

Condividi

Condividi

The Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva

Condividi

Condividi

Villa Farnesina

Location

Church of San Giorgio in Velabro

Location

Itineraries

Travel Info

Form contatti

[contact-form 5 "Customer Care_EN"]

Credits

ROMA CAPITALE DIPARTIMENTO GRANDI EVENTI, SPORT, TURISMO E MODA

Head of the Department

Patrizia Del Vecchio

Coordination

Francesca Cellamare

Tourism Area Coordinator

Carlo Guarino

Web Manager

Rosario Boccarossa

Social Media Manager

Elisabetta Giuliani

Web Editors

Marina Moretti

Luciana Pelosi

Cristina Ribacchi

Simonetta Salvioni

Social Media Editors

Laura Dal Pont

Pier Paolo Mancuso

Maria Teresa Penserini

Daniele Veroli

IT System Manager

Luca Pavone

Site Creation

Please note: some of the contents of Turismoroma come from the Tourism and Culture database of the city of Rome www.060608.it

Rome for you

Figs

Che figo! (lit. What a fig!) - So cool!

A first love is never forgotten: the fig is believed to be the oldest cultivated fruit in the Mediterranean area and has left evidence of its importance in art, culture and religion since the dawn of time. Just to give a few examples: in the Old Testament it was synonymous with wealth and abundance, for the ancient Egyptians it was a symbol of the victory over death, ancient Greeks attributed its birth to the god Dionysus and considered its fruits “worthy of nourishing orators and philosophers”. Plato was so fond of figs that he was nicknamed “fig eater” and advised his young students to eat plenty of them because, he said, “they boost intelligence”. In addition to being rich in sugar, they contain high levels of calcium, iron and potassium, phosphorus and vitamins, and have good antioxidant, energizing and anti-inflammatory properties.

A city founded on figs

Their sweetness and virtues did not fail to seduce the ancient Romans who over time spread their cultivation throughout the Italian peninsula and the whole Empire. After all, the fig tree was also connected to the foundation of Rome: legend has it that near a wild fig – the Ficus Ruminalis – the floating trough with Romulus and Remus came to rest and beneath the fig the she-wolf suckled and fed the twins. According to historians, after the demise of the old tree on the Palatine’s slopes another fig sprouted spontaneously in the Forum: the plant was considered a good omen and the fate of the city depended on its state of health, which explains why it was promptly replaced as soon as it dried up... And always under a fig tree the feasts of Juno Caprotina were celebrated on 7 July, an ancient all-female solemnity attended by handmaids and free women.

Fatal figs

Tender and utterly seductive, figs have won hearts but have also started wars: because of them Rome’s historical rival Carthage was destroyed. In the second century BC, “Carthago delenda est”, “Carthage must be destroyed” was the admonition constantly repeated by Marcus Porcius Cato, otherwise known as Cato the Censor, convinced that the Romans should never come to terms with their age-old enemy. Too dangerous and, above all, too close. A proof thereof? A basket of fresh figs coming straight from Carthage, exhibited as a powerful tool of persuasion to all the senators who were reluctant to a military intervention. But figs are also linked to the death of Cleopatra, the Egyptian queen famous in history as the lover of Julius Caesar and later of Marcus Anthony. Cleopatra loved figs so much that she wanted the asp with which she killed herself to be hidden among their leaves. At least according to what Plutarch says... Lastly, rumors had it that Augustus was killed with a poisoned fig that his wife Livia gave him.

In art and cuisine

Today, the varieties of figs run into the hundreds but Pliny already listed 29 of them, including the purple and extra sweet “Black Brogiotto”, the pot-bellied protagonist of many Renaissance still lifes. A basket filled with magnificent ripe green and black figs is shown in a famous fresco from Poppea’s Villa at Oplontis: since ancient times, figs inspired artists and food lovers alike. Suitable for young and old, and, according to Pliny, even able to reduce wrinkles, they accompanied desserts and cheeses, or were flavored with salt, vinegar and garum, a fish sauce. By boiling them, Romans produced the so-called “fig honey”, precious for sweetening food. Ancient recipes also include the special dried fig loin (to be pounded with feet) by Columella and the “iecur ficatum” by Apicius, the most famous gastronome in ancient Rome. This was a delicacy based on the liver of animals fattened with figs, and it was so fashionable that it also influenced the dictionary: not from “iecur” but from “ficatum” comes the word “fegato”, the Italian for “liver”.

How much is a dried fig worth

The fresh fig is a rare commodity that you can only get in the summer and early fall – with a smaller harvest in June, and a larger harvest from July to September. In order to preserve and eat fig fruits throughout the year, people soon learned to dry them: many dried figs have been found, for example, in the Herculaneum archeological site, stored in clay or glass containers. Ovid says dried figs, dates and honey were offered on New Year’s Eve to friends and relatives as a wish for the new year. But the Roman Empire itself was built on figs: Tacitus, in his Annales, explains that legionaries were paid with a handful of salt (hence the name salary) and dried figs, which were very useful in military campaigns since they are so nutrient dense. An old soldier, unable to defend Rome, was “not worth a dried fig”, an expression used still today to indicate someone or something that has no use.

Noble and popular

Emperor Augustus ate them with cheese and fish, Gallienus offered them in his sumptuous banquets but figs, plentiful and easily grown, were appreciated by less well-to-do classes due to their energetic properties, were included in the meals granted to slaves and have been a staple of farmers’ diets for centuries, so much so that they were called the bread of the poor. So, at the time of Emperor Diocletian, the cheapest product on the market was a paste obtained by pounding and mixing with aromatic herbs figs left to dry in the sun. Today, figs color and give flavor to every type of dish and continue to play a leading role, both in gourmet recipes and in simple yet sublime traditional dishes that the Romans still love: pizza and figs or prosciutto and figs.