As a famous Latin maxim quotes, “Nomina sunt consequentia rerum”, that is “names are the consequences of things”. Yet sometimes what reveals us the true essence and paints a vivid portrait of things are the nicknames with which they are promptly renamed. People’s imagination and inventiveness knows no borders and encircles the world: needless to say that, over the centuries, even public monuments and art works were used as targets.

Expressing a witty, light-hearted sense of humor and a wonderful capacity for synthesis, nicknames and mockeries have sometimes proved so effective as to be handed down from generation to generation and to impose themselves in common use. But they are also, after all, a form of love, a creative way to shorten distances and regain possession of those symbols that have helped give Rome an identity. We present you seven examples, in alphabetical order, to find out how the ability to find the right nickname can be an art by itself.

# 1 Angelo puntello, Angel acting as a prop - The church of Sant’Andrea della Valle was largely built between 1590 and 1650 by Giacomo Della Porta and Carlo Maderno, with the latter designing the marvelous dome, the second highest in Rome after St Peter’s. Eighteen small and large statues decorate its Baroque façade: one of them is an angel that is suspended on the left cornice and links the façade’s lower and upper storeys. On the opposite side to the right, there is an empty space, proving to be quite asymmetric. Legend says that, once carved, the angel aroused some controversy by the Roman people and was also criticized by Pope Alexander VII. Its author was Ercole Ferrata, a close collaborator of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, for whom he later carved one of the angels of the Sant’Angelo bridge. The artist refused to keep on working, declaring in a huff, that, if the Pope wanted another angel, he would have to carve it himself. The lonely angel, with one wing stretched up that seems to lean (some say support) the wall, provoked Pasquino’s caustic comment which gave birth to the nickname: “I would like to fly like a bird, but here I was placed to act as a prop”.

# 2 Confetto succhiato, Sucked Sugar-Almond - In the district once inhabited by wealthy Tuscan families, works for the construction of the basilica of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini lasted over three centuries, from 1519 to 1734. Some of the best architects of the time took part at the competition launched at the beginning of the 16th century by Pope Leo X, who had resumed a project entrusted by Julius II to Bramante and interrupted for the death of the pope. Jacopo Sansovino won the competition but he was soon replaced by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and later by Giacomo Della Porta. In 1609 Carlo Maderno took over as architect and designed, among other things, the characteristic dome set on a high octagonal drum and finished off by a graceful lantern. Completed in 1614, the long and narrow dome testifies to Maderno’s balanced and refined sensitivity but ended up being jokingly called the “Sucked Sugar-Almond” because of its elongated shape. And under it rests its author, buried together with Francesco Borromini inside the church.

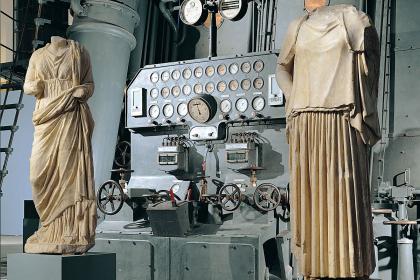

# 3 Dinosauro, Dinosaur - In the late 1930s, as part of the planning for the 1942 World’s Fair, it was decided to rebuild in a monumental style the “old” Termini Station, inaugurated in 1874 among the fields and vineyards of the Esquiline Hill. It was designed by Angiolo Mazzoni but works were soon halted by the war. Reprised by two new groups of architects, they were then completed in December 1950, in a completely changed political and cultural climate. Dating back to these years is one its most characterizing elements: the long concrete canopy, designed by architect Montuori, which extends beyond the glass volume of the ticket offices. Seen from the side, its lines seem to reproduce the tail, back and neck of a great prehistoric reptile and in the 1960s Romans nicknamed it the “Dinosaur”. Its shape actually frames the profile of the Agger of the Servian Wall, in a perfect continuity between ancient and modern times. Indeed, the motto of the project of the architects who conceived the structure was “Servius Tullius takes the train”.

# 4 Macchina da scrivere, Typewriter - “A bulky mountain of marble”, as journalist and politician Antonio Cederna defined it, honors the first king of Italy: the construction of the Vittoriano, entrusted in 1885 to the young architect Sacconi and then completed by Pio Piacentini, Gaetano Koch and Manfredo Manfredi, upset the historic geography of the city center and led to the destruction of important Medieval and Renaissance buildings. Monumental and out of scale, it was immediately seen as an eyesore, partly because of the decision to replace the Travertine stone envisaged in the project with the brilliant white Botticino marble. The complex was therefore given several and irreverent nicknames, ranging from “the typewriter”, for the colonnade that resembles its keys, to “the wedding cake" or to “the dentures”, and in the 1908s it was even at the center of a peculiar process to prompt its demolition. What is certain is that it catches the eye, besides being one of the symbols of Rome and a must-see for tourists. Even more impressive is the panorama from its very top level, reached by glass elevators that were installed in 2007.

# 5 Monte d’Empietà, Mount of Impiety - A Mount of Piety is an institutional pawnbroker run as a charity, a 15th-century institution originated in Italy. The Roman Monte di Pietà was founded later, in the first half of the 16th century at the time of Pope Paul III, and in 1603 it was moved to Palazzo Santacroce Aldobrandini. Architects of the likes of Francesco Borromini and Carlo Maderno contributed to adapt the building to the new use, enlarging the façade created by Il Mascherino for Cardinal Prospero Santacroce. The chapel dates back to this age: a jewel of Baroque art with polychrome marbles and gilded stuccos. Construction of the building continued until 1730 and in 1759 another building was added, the “Casa Grande” of the Barberini family, who in the meantime had moved to their new palace on the Quirinal Hill. People in need were however not very impressed by such beauty and grandeur: although the Mount of Piety was born to combat usury and help the poor, as the plaque designed by Carlo Maderno states, it was soon sarcastically renamed “Mount of Impiety” by the Romans, probably not satisfied with the estimates or interest rates applied.

# 6 Palazzaccio, Bad Palace - A little-loved frail giant, popularly known with the pejorative nickname of Palazzaccio or Bad Palace. Together with the Vittoriano, the Palace of Justice is one of the grandest additions to the city following the proclamation of Rome as the Italian capital, but it was born under a bad star. Its architect Guglielmo Calderini insisted to build it on the left side of the Tiber, in the then-new Rione Prati. The excavations for its foundations unearthed several archaeological finds – including an articulated doll, now at the Centrale Montemartini museum, in the sarcophagus of the young Crepereia Tryphaena – but the alluvial soil caused slowdowns and structural instability problems. The palace was thus inaugurated only 22 years later, in 1911, receiving heavy critics. Some say that Calderini was so distraught by his failure that he committed suicide. Completely covered with Travertine limestone and hyper-decorated, disliked for its function and under parliamentary investigation for alleged corruption, it has long been treated with contempt but is now part of the city’s skyline and an historical testimony of an era. Thus, when in the 1960s new instability issues elicited debate on its demolition, it was rightly pardoned and restored.

# 7 Pulcino della Minerva, Minerva’s Chick – There’s a stone elephant in the churchyard of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, named after a no longer extant temple dedicated to the ancient Roman goddess of knowledge. In 1665, a small obelisk was unearthed in the garden of the nearby convent and Pope Alexander VII Chigi wanted it to be erected in the square. Several architects including the Dominican priest Giuseppe Paglia submitted their projects for the obelisk’s base but the commission was given to Gian Lorenzo Bernini: among the many designs presented, the pope chose the elephant as an allegorical representation of fortitude. In the sculptor’s original plan, the obelisk would have fully rested on the elephant’s four legs but the Dominicans, led by Father Paglia, convinced the pope that this put the stability of the obelisk at risk. A stone cube was thus inserted under the belly of the pachyderm as a support, with the result of giving the statue a rather stout look. Stocky and with short legs, the little elephant became the object of mottos and jokes and was nicknamed by the Romans the “Porcino della Minerva”, i.e. Minerva’s Piglet, which later became “Purcino” and therefore “Pulcino”. The elephant’s rear pointing towards the Dominican convent, with the tail slightly shifted to the left, was according to rumors a small revenge of the great sculptor.

Basilica of Sant'Andrea della Valle

Condividi

Condividi

Sant'Angelo bridge

Condividi

Condividi

The Basilica of San Giovanni Battista dei Fiorentini

Condividi

Condividi

Servian Walls

Condividi

Condividi

Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II (Vittoriano)

Condividi

Condividi

The terraces of the Vittoriano

Condividi

Condividi

Palazzo Santacroce Aldobrandini (or of the Monte di Pietà)

Condividi

Condividi

The Galleria Nazionale di Arte Antica - Palazzo Barberini

Condividi

Condividi

The Palace of Justice

Condividi

Condividi

Centrale Montemartini

Condividi

Condividi

The Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva

Condividi

Condividi